Cornish language

| Cornish | ||

|---|---|---|

| Kernewek, Kernowek | ||

| Pronunciation | [kərˈnuːək] | |

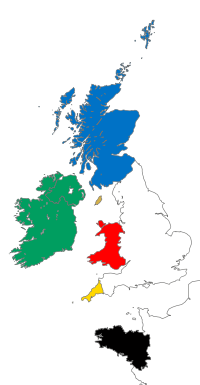

| Spoken in | ||

| Region | ||

| Total speakers | 2,000 fluent[1] | |

| Language family | Indo-European | |

| Writing system | Latin alphabet | |

| Official status | ||

| Official language in | ||

| Regulated by | Cornish Language Partnership | |

| Language codes | ||

| ISO 639-1 | kw | |

| ISO 639-2 | cor | |

| ISO 639-3 | cor | |

| Linguasphere | ||

| Note: This page may contain IPA phonetic symbols in Unicode. | ||

Cornish (Kernewek or Kernowek) is a Brythonic Celtic language and a recognised minority language of the United Kingdom, spoken in Cornwall. The language continued to function as a community language in parts of Cornwall until the late 18th century[2], and a process to revive the language was started in the early 20th century, continuing to this day.

The revival of Cornish began in 1904 when Henry Jenner, a Celtic language enthusiast, published his book Handbook of the Cornish Language. In his work he observed, "There has never been a time when there has been no person in Cornwall without a knowledge of the Cornish language."[3] Jenner's work was based on Cornish as it was spoken in the 18th century, although his pupil Robert Morton Nance later steered the revival to the style of the 16th century, before the language became more heavily influenced by English. This set the tone for the next few decades; as the revival gained pace, learners of the language disagreed on which style of Cornish to use, and a number of competing orthographies were in use by the end of the century.

Nevertheless, many Cornish language textbooks and works of literature have been published over the decades, and an increasing number of people are studying the language.[4] Recent developments include Cornish music[5], independent films[6] and children's books. A small number of children in Cornwall have been brought up to be bilingual native speakers,[7] and the language is taught in many schools.[8] Cornish gained official recognition under the European Charter for Regional or Minority Languages in 2002,[9] and in 2008 a Standard Written Form was agreed in an attempt to unify the orthographies and move forward the revival.[10] The first Cornish language crèche opened in 2010.[11]

Contents |

Current status

Revived language

In the 20th century a conscious effort was made to revive Cornish as a language for everyday use in speech and writing (see below for further details about the dialects of modern Cornish).

This revival can be traced to the work of Jenner, who in 1904 published his work A Handbook of the Cornish Language. This formed the basis for the language revival and learning. In his work he observed, "There has never been a time when there has been no person in Cornwall without a knowledge of the Cornish language."[3]

The number of Cornish speakers is growing.[4] Determining a figure for the number of Cornish speakers depends on how the ability to speak the language is defined. One figure for the mean amount of people who know a few basic words, such as knowing that "Kernow" means "Cornwall", was 300,000; the same survey gave the figure of people able to have simple conversations at 3,000.[12] The Cornish Language Strategy project commissioned research to provide quantitative and qualitative evidence for the number of Cornish speakers: due to the success of the revival project it was estimated that 2,000 people were fluent (surveyed in spring 2008), an increase from the estimated 300 people who spoke Cornish fluently suggested in a study by Kenneth MacKinnon in 2000.[1][13][14] A few people under the age of 30 have been brought up to be bilingual in Cornish and English.

Cornish exists in place names, and a knowledge of the language helps the understanding of old place names. Many Cornish names are adopted for children, pets, houses and boats. There is now an increasing amount of Cornish literature, in which poetry is the most important genre, particularly in oral form or as song or as traditional Cornish chants historically performed in marketplaces during religious holidays and public festivals and gatherings. Cornwall Council (Cornish: Konsel Kernow) has a policy of supporting the language, and recently passed a motion in favour of it being specified within the European Charter for Regional or Minority Languages.

There are regular periodicals solely in the language such as the monthly An Gannas, An Gowsva, and An Garrick. BBC Radio Cornwall and Pirate FM have regular news broadcasts in Cornish, and sometimes have other programmes and features for learners and enthusiasts. Local newspapers such as the The Western Morning News regularly have articles in Cornish, and newspapers such as The Packet, The West Briton and The Cornishman also support the movement.

The language has financial sponsorship from many sources, including the Millennium Commission. A number of language organisations exist in Cornwall including (in alphabetical order) Agan Tavas (Our Language), the Cornish sub-group of the European Bureau for Lesser-Used Languages, Gorseth Kernow, Kesva an Taves Kernewek (the Cornish Language Board), Kowethas an Yeth Kernewek (the Cornish Language Fellowship), and Teere ha Tavas (Land and Language). One organisation, Dalleth (now defunct), promoted the language to pre-school children. There are many popular ceremonies, some ancient, some modern, which use the language or are entirely in the language. The language has been officially recognised as one of the historical regional and minority languages in Europe (see European recognition below).

A decision to brand Cornish extinct, made by linguists working for UNESCO's Atlas of World Languages, was widely criticised[15]. The Atlas' editor, Christopher Moseley, says a new category of "being revived" is being considered for the next edition.[16]

European recognition

On 5 November 2002, in answer to a Parliamentary Question, Local Government and Regions Minister Nick Raynsford said:

After careful consideration and with the help of the results of an independent academic study on the language commissioned by the government, we have decided to recognise Cornish as falling under Part II of the European Charter for Regional or Minority Languages.The government will be registering this decision with the Council of Europe.

The purpose of the Charter is to protect and promote the historical regional or minority languages of Europe.It recognises that some of these languages are in danger of extinction and that protection and encouragement of them contributes to Europe's cultural diversity and historical traditions.

This is a positive step in acknowledging the symbolic importance the language has for Cornish identity and heritage.

Cornish will join Welsh, Scottish Gaelic, Irish, Scots and Ulster Scots as protected and promoted languages under the Charter, which commits the government to recognise and respect those languages.

Officials will be starting discussions with Cornwall Council and Cornish language organisations to ensure the views of Cornish speakers and people wanting to learn Cornish are taken into account in implementing the Charter.

Government funding for the Cornish language

In June 2005, after much pressure from language groups and others such as the Gorseth Kernow, the government allocated £80,000 per year for three years of direct central government funding to the Cornish language. There have been complaints however that in the same period Ulster Scots is being allocated £1,000,000 per year of direct government funding. This comes after the British government acknowledged in its 1st European Charter for Regional or Minority Languages compliance report that: "There are no current demands from within the school system for Ulster-Scots to be taught as a language. There have been concerns that while the ECRML Level II Cornish language remains in the slow lane, the Ulster-Scots language is to be made a ECRML Level III language."[17][18]

Classification

Cornish is one of the Brythonic languages, which constitute a branch of the Celtic languages. This branch also includes the Welsh, Breton, the extinct Cumbric, and perhaps the hypothetical Ivernic languages. The Scottish Gaelic, Irish, and Manx languages are part of the separate Goidelic branch. Cornish shares about 80% basic vocabulary with Breton, 75% with Welsh, 35% with Irish, and 35% with Scottish Gaelic.

History

Historical background

Cornish evolved from the British language spoken throughout Britain south of the Firth of Forth during the Iron Age and Roman period. Some scholars have proposed that the language split into Western and Southwestern dialects, perhaps after the Battle of Deorham in about 577. This Southwestern Brythonic dialect later evolved into Cornish as well as Breton, while Western Brythonic became the ancestor to Welsh and Cumbric.[19]

The proto-Cornish language developed after the Southwest Britons of Somerset, Dorset, Devon and Cornwall became linguistically separated from the West Britons of later Wales after the Battle of Deorham in about 577. The area controlled by the Southwest Britons was progressively reduced by the expansion of Wessex over the next few centuries; in 927 Athelstan drove the south west Celts out of Exeter and in 936 he set the east bank of the Tamar as the boundary between Anglo-Saxon Wessex and Celtic Cornwall.[20] "Exeter was cleansed of its defilement by wiping out that filthy race" (William of Malmesbury, writing around 1120) [20]. There is no record of him taking his campaigns into Cornwall. It seems probable that Hywel, King of the Cornish, agreed to pay tribute to Athelstan and thus avoided more attacks and maintained a high degree of autonomy.[21] However, the Cornish language continued to flourish well through the Middle Ages, reaching a peak of about 39,000 speakers in the 13th century.[22] However, the number of Cornish speakers is thought to have declined thereafter.

The earliest written record of the Cornish language, dating from the 9th century AD, is a gloss in a Latin manuscript of De Consolatione Philosophiae by Boethius, which used the words ud rocashaas. The phrase means "it (the mind) hated the gloomy places".[23][24]

Tudor Period to Restoration

In the reign of Henry VIII we have an account given by Andrew Borde in his Boke of the Introduction of Knowledge, written in 1542. He states, "In Cornwall is two speches, the one is naughty Englysshe, and the other is Cornysshe speche. And there be many men and women the which cannot speake one worde of Englysshe, but all Cornyshe." [25]

At the time of the Prayer Book rebellion of 1549, which was a reaction to Parliament passing the first Act of Uniformity, people in many areas of Cornwall did not speak or understand English (the intention of the Act was to replace worship in Latin with worship in English, which was known, by the lawmakers, not to be universally spoken throughout England. Instead of simply banning Latin, however, the Act was framed so as to enforce English). In 1549, this imposition of a new language was sometimes a matter of life and death: over 4,000 people who protested against the imposition of an English Prayer book were massacred by the King's army. Their leaders were executed and the people suffered numerous reprisals.

The rebels' document claimed they wanted a return to the old religious services and ended 'We the Cornishmen (whereof certain of us understand no English) utterly refuse this new English' (altered spelling). Edward Seymour, Duke of Somerset, replied to the Cornishmen, inquiring as to why they should be offended by services in English when they had them in Latin, which they also did not understand. Through many factors, including loss of life and the spread of English, the Prayer Book Rebellion proved a turning-point for the Cornish language. Indeed, some recent research has suggested that estimates of the Cornish-speaking population prior to the rebellion may have been low, making the decline even more drastic.

By this time the language must already have been in decline from its earlier heyday, and the situation worsened over the course of the next century. Richard Carew in his 1602 work The Survey of Cornwall, notices the almost total extirpation of the Cornish language in his days. He says; The principal love and knowledge of this language liveth in Dr. Kennall, the civilian, and with him lieth buried.[26] Towednack is claimed to be the location of the last church in which services were conducted in the Cornish language (in 1678), though the same claim has been made for Ludgvan and for Landewednack.[27] Carew also said Most of the inhabitants can speak no word of Cornish, but very few are ignorant of the English; and yet some so affect their own, as to a stranger they will not speak it; for if meeting them by chance, you inquire the way, or any such matter, your answer shall be, "Meea navidna caw zasawzneck", "I can speak no Saxonage". [28]

18th-19th centuries

It will probably be impossible to establish who the definitive "last native speaker" of Cornish was owing to the lack of extensive research done at the time and the obvious impossibility of finding audio recordings dating from the era. There is also difficulty with what exactly is meant by "last native speaker", as this has been interpreted in differing ways. Some scholars prefer to use terms such as "last monoglot speaker", to refer to a person whose only language was Cornish, "last native speaker", to refer to a person who may have been bilingual in both English and Cornish and furthermore, "last person with traditional knowledge", that is to say someone who had an extensive knowledge of Cornish from traditional sources but had not studied the language per se.

The last known monoglot Cornish speaker is believed to have been Chesten Marchant, who died in 1676 at Gwithian. It is not known when she was born. William Scawen, writing in the 1680s, states that Marchant had a "slight" understanding of English and had been married twice.[29]

In 1742, Captain Samuel Barrington of the Royal Navy made a voyage to Brittany, taking with him a Cornish sailor of Mount's Bay. He was astonished that this sailor could make himself understood in Breton. In 1768, Barrington's brother Daines Barrington searched for speakers of the Cornish language and at Mousehole found Dolly Pentreath, a fish seller then aged about 82, who "could speak Cornish very fluently". In 1775, he published an account of her in the Society of Antiquaries' journal Archaeologia, entitled On the Expiration of the Cornish Language. He reported that he had also found at Mousehole two other women, some ten or twelve years younger than Pentreath, who could not speak Cornish readily, but who understood it.[30] Pentreath, who died in 1777, is popularly claimed to be the last native speaker of Cornish. Notwithstanding her reported last words, "Me ne vidn kewsel Sowsnek!" ("I will not speak English!"), she spoke at least some English.

Peter Berresford Ellis poses the question of who was the last speaker of the language, and replies that "We shall never know, for a language does not die suddenly, snuffed out with one last remaining speaker... it lingers on for many years after it has ceased as a form of communication, many people still retaining enough knowledge from their childhood to embark on conversations..." He also notes that in 1777 John Nancarrow of Market Jew, not yet forty, could speak the language, and that into the next century some Cornish people "retained a knowledge of the entire Lord's Prayer and Creed in the language".[31]

The Reverend John Bannister stated in 1871 that "The close of the 18th century witnessed the final extinction, as spoken language, of the old Celtic vernacular of Cornwall".[32] However, there is some evidence that Cornish continued, albeit in limited usage by a handful of speakers, through the late 19th century. In 1875 six speakers all in their sixties were discovered.[33] The farmer John Davey, who died in 1891 at Boswednack, Zennor, may have been the last person with some traditional knowledge of Cornish.[34] However, other traces survived. Fishermen in West Penwith were counting fish using a rhyme derived from Cornish into the 20th century.[35]

Sources on Traditional Cornish

The Southwestern Brythonic, or Southwestern Brittonic, language evolved into Cornish, shrinking from the whole southwest of England into the western tip of Cornwall with time. Kenneth H. Jackson divided this long period into several sub-periods having different linguistic innovations.

"Primitive Cornish" existed between about 600 and 800 AD but nothing survives from this time. The "Old Cornish" period was between 800 and 1200 AD, for which there is a Cornish-Latin dictionary (the Vocabularium Cornicum or Cottonian Vocabulary; MS. Cotton Vespasian A.xiv)[36] and various 10th century glosses in Latin manuscripts such as the Bodmin manumissions giving the Cornish names of freed slaves.

Prophetiae Merlini (Prophecy of Merlin) a manuscript dating from about 1133 written in Latin by John of Cornwall, contains some margin notes in the Cornish language. The original manuscript is unique and currently held in a codex at the Vatican Library. The manuscript attracted little attention from the scholarly world until 1876 when Whitley Stokes undertook a brief analysis of the Cornish and Welsh vocabulary found in John's marginal commentary.[37]

The "Middle Cornish" period between 1200 and 1578 has many sources of information, mostly religious texts. There are about 20,000 lines of text in total. Various plays were written by the canons of Glasney College intended to educate the Cornish people about the Bible and the Celtic saints.

The "Late Cornish" period from 1578 to about 1800 has fewer sources of information on the language. In this period there was considerable input from the English language. In 1776 William Bodinar, who had learnt Cornish from fishermen, wrote a letter in Cornish which was probably the last prose in the language. However, the last verse was the Cranken Rhyme written in the late 19th century by John Davey of Boswednack.

William Bodinar's letter 1776

This is an example of Cornish written by the hand of a native speaker [1]. The text is also interesting from a sociolinguistic point of view in that Bodinar speaks about the contemporary state of the Cornish language in 1776.

| Bodinar's original spelling | Curnoack Nowedga or Modern Cornish transcription |

|---|---|

Bluth vee try egance a pemp. |

Bluth vee ewe try egence a pemp. |

| Standard Written Form transcription (Late variant) |

Kernowek Standard transcription |

Bloodh ve ew trei ugens ha pymp. |

Bloodh vy yw try ugans ha pymp. |

| Kernewek Kemmyn or Common Cornish translation |

English translation |

[Ow] bloedh vy [yw] tri ugens ha pymp. |

I'm sixty-five years old. |

Placename evidence

Further information on traditional Cornish can be obtained from the place names (toponyms) of Cornwall that not only reflect meaning but also language change throughout the period in which Cornish was spoken in Cornwall. The place names have been analysed into elements for which meanings have been inferred.

Rise of Cornish studies

William Scawen produced an epic manuscript on the declining Cornish language that continually evolved until he died in 1689, aged 89. He was the first person to realise the language was dying out and wrote detailed manuscripts which he started working on when he was 78. The only version that was ever published was a short first draft, but the final version, which he worked on until his death, is hundreds of pages long. At the same time a group of scholars, led by John Keigwin (nephew of William Scawen), of Mousehole, tried to preserve and further the Cornish language. They left behind a large number of translations of parts of the Bible, proverbs and songs. This group was contacted by the Welsh linguist Edward Lhuyd who came to Cornwall to study the language.[38][39][40][41]

Early Modern Cornish was the subject of a study published by Lhuyd in 1707, and differs from the medieval language in having a considerably simpler structure and grammar. Such differences included the wide use of certain modal affixes that, although out of use by Lhuyd's time, had a considerable effect on the word-order of medieval Cornish. The medieval language also possessed two additional tenses for expressing past events and an extended set of possessive suffixes. Edward Lhuyd theorises that the language of this time was heavily inflected, possessing not just the genitive, ablative and locative cases so common in Early Modern Cornish, but also dative and accusative cases, and even a vocative case, although historical references to this are rare.

John Whitaker the Manchester-born rector of Ruan Lanihorne, studied the decline of the Cornish language. In his 1804 work the Ancient Cathedral of Cornwall he concluded that: "[T]he English Liturgy, was not desired by the Cornish, but forced upon them by the tyranny of England, at a time when the English language was yet unknown in Cornwall. This act of tyranny was at once gross barbarity to the Cornish people, and a death blow to the Cornish language.".[42]

Robert Williams published the first comprehensive Cornish dictionary in 1865, the Lexicon Cornu-Britannicum. As a result of the discovery of additional ancient Cornish manuscripts, 2000 new words were added to the vocabulary by Whitley Stokes in A Cornish Glossary. William C. Borlase published Proverbs and Rhymes in Cornish in 1866 while A Glossary of Cornish Place Names was produced by John Bannister in the same year. Dr Frederick Jago published his English-Cornish Dictionary in 1882.

Revival

During the 19th century the Cornish language was the subject of antiquarian interest and a number of lectures were given on the subject and pamphlets on it were published. In 1904 the Cornish Revival began with publication of Henry Jenner's Handbook of the Cornish Language. The publication included Cornish spelling as it was last used when Cornish was a community language in the 18th century. This orthography had never been standardised and so had many variants. In response to this a unified system of spelling was needed, and, in 1929 Robert Morton Nance standardised a form of Cornish with Unified Cornish based upon written Middle Cornish from the Medieval period. Nance was a purist who tended to prefer older ‘Celtic’ forms rather than the historically more recent forms deriving from Middle and Early Modern English. Nevertheless, Nance's system became the standard form for Cornish and remained so until the 1980s when people started to challenge Unified Cornish feeling that it too was flawed.[43]

Ken George studied the sounds of Cornish based on the early works of Lluyd and had sought to create a bridge between Unified and Late Cornish- as had been used by Henry Jenner but instead George devised a new system on realising the flaws in Unified Cornish. This was held to have the advantage of the written word accurately representing the spoken word based upon George’s own theories.George's system, or the phonemic system as it later became known was officially named Kernewek Kemmyn (Common Cornish) and after a one year discussion the Cornish Language Board agreed to adopt it in 1987. This decision caused division in the Cornish language community, especially since people had been using Nance's old system for years and were unfamiliar with the new one.[43]

These divisions continued when Kernewek Kemmyn was itself challenged in 1995 by Nicholas Williams in his book "Cornish Today" that listed 26 major flaws in Kernewek Kemmyn and devised yet another new form of Unified Cornish, namely, "Unified Cornish Revised". A dictionary of Unified Cornish Revised appeared later, selling enough to merit a second edition, and to date this is considered the most comprehensive dictionary of the Cornish language. A reply to "Cornish Today" appeared soon after in the book "Kernewek Kemmyn – Cornish for the Twenty First Century" by Ken George and Paul Dunbar to which a reply appeared in 2007.[43]

In order to end this ceaseless in-fighting and polemics that many feel have hindered the Cornish language's revival, it was decided to aim for a Standard Written Form once and for all. The fourth and final Standard Written Form draft was generated on 30 May 2008. [44]. Another step forward came on 17 June 2009 when it was reported that for the unity and future of the Cornish language a decision was made by the bards of the Gorseth Kernow at their annual meeting under the leadership of Grand Bard Vanessa Beeman. By an overwhelming majority and after two decades of debate they adopted the Standard Written Form (SWF) for their ceremonies and correspondence. From the earliest days under Grand Bards Henry Jenner and Morton Nance the 'Unified Form' has been used for the Gorsedd ceremony.[45]

Forms of Revived Cornish

Unified Cornish

The first successful attempt to revive Cornish was largely the work of Henry Jenner and Robert Morton Nance in the early part of the twentieth century. Jenner published his "Handbook of the Cornish Language" in 1904 while Nance published "Cornish For All" in 1929. A. S. D. Smith produced Lessons in Spoken Cornish in 1931.

The resulting system was called Unified Cornish or UC (Kernewek Uny[e]s, KU) and was based mainly on Middle Cornish (the language of the fourteenth and fifteenth centuries — a high point for Cornish literature), with a standardised spelling and an extended vocabulary based largely on Breton and Welsh. A dictionary of Unified Cornish was published by Nance in the 1930s. For many years, this was the "modern Cornish" language, and many people still use it today.

Shortcomings in Unified Cornish had to do in part with the stiff and archaizing literary style Nance had employed, and in part with a realisation that Nance's phonology lacked some distinctions which must have existed in traditional Cornish. In the 1970s, Tim Saunders raised a number of issues of communicative efficiency, but his initiative had no influence and later developments are entirely independent.

Modern Cornish or Revived Late Cornish

In the early 1980s, Richard Gendall, who had worked with Nance, published a new system based on the works of writers such as Nicholas Boson and John Boson, William Rowe, Thomas Tonkin and others, some of the last Cornish writers before the language's extinction. This system, called Modern Cornish (Kernûak Nowedga) by its proponents, differs from Unified Cornish in using the English-influenced orthographies of the 17th and 18th centuries, though there are also differences of vocabulary and grammar. It is sometimes called "Revived Late Cornish" or RLC as well. Writers of Late Cornish often wrote Cornish using the English orthographic equivalent of the nearest equivalent English sound. For instance, the word for 'good' typically spelt dâ 'good' could also be written daa, and the word for 'month' could be spelt mîz or meez. The need for standard spelling when learning a language has led the Cornish Language Council to adopt the Revived Late Cornish spelling standardised by Gendall and Neil Kennedy. This makes sparing use of accents (as did writers of Modern Cornish at the time).

Kernewek Kemmyn or Common Cornish

In 1986 Ken George developed a revised orthography (and phonology) for Revived Cornish, which became known as Kernewek Kemmyn or KK (lit. Common Cornish). It was subsequently adopted by the Cornish Language Board as their preferred system. It retained a Middle Cornish base but made the spelling more systematic by applying phonemic orthographic theory, and for the first time set out clear rules relating spelling to pronunciation. The revised system is claimed to have been taken up enthusiastically by the majority of Cornish speakers and learners, and advocates of this orthography claim that it was especially welcomed by teachers. Nevertheless, many Cornish speakers chose to continue using Unified Cornish. Despite later criticism by Nicholas Williams (see below), Kernewek Kemmyn has retained the support of many active Cornish speakers.

Unified Cornish Revised

In 1995 an alternative revision of Unified Cornish known as Unified Cornish Revised or UCR (Kernowek Unys Amendys, KUA) was proposed by Nicholas Williams. UCR built on traditional Unified Cornish, making the spellings regular while keeping as close as possible to the orthographic practices of the medieval scribes. The rationale behind UCR was that only attested Cornish can serve as a guide to its phonology, and that other attempts at regularisation had on the one hand introduced alien elements and on the other hand not known how to interpret the variations in extant material, which it turned to explain in accordance with the assumptions of nineteenth-century Middle European philology. In common with Kernewek Kemmyn, UCR made use of Tudor and Late Cornish prose materials unavailable to Nance. Williams published his English-Cornish Dictionary in this orthography in 2000; the second edition was published in 2006. Like the other orthographies, UCR also has its adherents and its detractors.

Unification projects

In practice these different written forms do not prevent Cornish-speakers from communicating with each other effectively. Cornish has been successfully revived as a viable language for communication. Nevertheless there is still much scope for improving the standard and accuracy of the spoken language. The language is spoken mainly with the older generations, but is currently being taught at some Cornish primary and secondary schools.

In response to the orthographic mayhem, the Cornish Language Partnership has initiated a period of review. In 2007 an independent Cornish Language Commission consisting of sociolinguists and linguists from outside of Cornwall was formed to review the four existing forms (UC, RLC, KK, and UCR) and consider whether any of those could be suitable to be a Single Written Form for Cornish, or whether a new fifth form should be adopted. Two groups made proposals of compromise orthographies.

- The UdnFormScrefys (Single Written Form) Group proposed an orthography called Kernowek Standard (KS) which is based on traditional orthographic forms and also has a clear relation between spelling and pronunciation, taking both Middle Cornish and Late Cornish dialects of Revived Cornish into account.[46] Since the publication of the Standard Written Form, KS evolved to become a set of proposed amendments to the SWF. For more information, see Kernowek Standard.

- Two members of the CLP's Linguistic Working Group, Albert Bock and Benjamin Bruch, proposed another orthography called Kernowek Dasunys (KD) which endeavours to reconcile UC, KK, RLC, and UCR orthographies.[47]

Standard Written Form

In May 2008 the Partnership agreed on a single written form to be known as Standard Written Form (SWF), to be used by Cornwall Council for education and public life.[48][49] The Cornish Language Partnership has specified that Furv Skrifys Savonek (FSS) is the SWF translation for Standard Written Form. Users of UCR and KS prefer the term Form Screfys Standard.[46]

On Friday, 9 May 2008, the Cornish Language Partnership met with the specification for the Standard Written Form as the main item on the agenda. All four Cornish language groups, Unified Cornish, Unified Cornish Revised, Common Cornish and Modern Cornish were represented at this meeting. Reactions were mixed from the various language groups, Kowethas an Yeth Kernewek, Cussel an Tavaz Kernûak, Kesva an Taves Kernewek and Agan Tavas, but the majority wanted resolution and acceptance. The Cornish Language Partnership said that it would 'create an opportunity to break down barriers and the agreement marked a significant stepping stone in the Cornish language.'. The vote to ratify the SWF was carried and on 19 May 2008 it was announced that the single written form had been agreed. Eric Brooke, chairman of the Cornish Language Partnership, said: "This marks a significant stepping-stone in the development of the Cornish language. In time this step will allow the Cornish language to move forward to become part of the lives of all in Cornwall."[50][51][52]

Phonetics and phonology

The pronunciation of Cornish is based on the records of the linguist Edward Lhuyd who visited Cornwall in 1700. The traditional texts are also used to extract the pronunciation, since many early texts are poems and many of the later texts were written phonetically due to the lack of both an orthographic standard and an education in Cornish. The traditional Cornish dialect and accent of English is also used for clues as to the pronunciation, and has been shown to match phonological characteristics of the traditional language.

Consonants

This is a table of the phonology of Revived Cornish as recommended for the pronunciation of Unified Cornish Revised (UCR) orthography, using symbols from the International Phonetic Alphabet (IPA).

| bilabial | labio- dental |

dental | alveolar | post- alveolar |

palatal | labio-velar | velar | glottal | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| plosive | p b | t d | k ɡ | ||||||

| nasal | m | n | ŋ | ||||||

| fricative | f v | θ ð | s z | ʃ ʒ | x | h | |||

| approximant | ɹ | j | ʍ w | ||||||

| lateral approximant | l |

Vowels

These are tables of the phonology of Revived Cornish as recommended for the pronunciation of Kernowek Standard (KS) orthography, using symbols from the International Phonetic Alphabet (IPA).

| Front | Near- front | Central | Near- back | Back | ||

| Close |

|

|||||

| Near-close | ||||||

| Close-mid | ||||||

| Mid | ||||||

| Open-mid | ||||||

| Near-open | ||||||

| Open | ||||||

| Front | Near- front | Central | Near- back | Back | ||

| Close |

|

|||||

| Near-close | ||||||

| Close-mid | ||||||

| Mid | ||||||

| Open-mid | ||||||

| Near-open | ||||||

| Open | ||||||

Speakers who prefer a later pronunciation merge the rounded vowels with the unrounded one.

Grammar

Cornish is a member of the Celtic branch of the Indo-European family of languages, and shares many of the characteristics of the other Insular Celtic languages. These include:

- Initial consonant mutation. The first sound of a Cornish word may change according to grammatical context. As in Breton, there are four types of mutation in Cornish (compared to three in Welsh and two in Irish), Manx and Gaelic. These are known as soft (b -> v, etc.), hard (b -> p), aspirate (b unchanged, t -> th) and mixed (b -> f).

| Unmutated consonant |

Soft mutation |

Aspirate mutation |

Hard mutation |

Mixed mutation |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| p | b | f | - | - |

| t | d | th | - | - |

| c, k | g | h | - | - |

| b | v | - | p | f |

| d | dh | - | t | t |

| g1 | disappears | - | c, k | h |

| g² | w | - | c | wh |

| gw | w | - | qw | wh |

| m | v | - | - | f |

| ch | j | - | - | - |

1 Before unrounded vowels (i, y, e, a), l, and r + unrounded vowel.

² Before rounded vowels (o, u), and r + rounded vowel.

- inflected (or conjugated) prepositions. A preposition combines with a personal pronoun to give a separate word form. For example, gans (with, by) + my (me) -> genef; gans + ef (him) -> ganso.

- No indefinite article. Cath means "cat" or "a cat" (there is, however a definite article: an gath means "the cat").

Pronouns

Personal pronouns (Late Cornish, SWF)

| Person | Singular | Plural |

|---|---|---|

| First | me | nei |

| Second | te, che | whei |

| Third | ev, 'e (masc.), hei (fem.) |

anjei, jei |

Dialects

Traditional Cornish would have probably had regional varieties, but due to the nature of revival, modern varieties have more to do with differences of opinion.

There are, essentially, four orthographic 'dialects' of Revived Cornish, but in linguistic terms, Unified Cornish and Common Cornish reflect Middle Cornish grammar and pronunciation while Revived Late Cornish favours Late Cornish grammar and punctuation. UCR stands somewhere between but closer to the Middle Cornish end of the spectrum. The two new proposed compromise orthographies, Kernowak Standard and Kernowek Dasunys attempt to represent both dialects of Revived Cornish.

It is also possible that a variety of Cornish was spoken in Devon as late as the 14th century: Then President of the Devonshire Association, Sir Henry Duke, said in 1922 that "various writers have made (assertions) of the continuance of British occupancy and of the British tongue in South and West Devon to a time well within the reigns of the Plantagenets. Risdon, for example, says that the Celtic tongue was spoken throughout the South Hams in Edward the First's time".

Some people from Devon have begun to learn a language based on Joseph Biddulph's booklet, A handbook of Westcountry Brythonic, which attempts to recreate the hypothetical southwestern Brythonic tongue which would have been spoken in the southwestern peninsula in around 700AD.

Examples

Comparison tables

This table compares the spelling of some Cornish words in different orthographies (Unified Cornish, Unified Cornish Revised, Kernewek Kemmyn, Revived Late Cornish, the Standard Written Form[53], and Kernowek Standard).

| UC | UCR | KK | RLC | SWF | KS | English |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Kernewek | Kernowek | Kernewek | Kernûak | Kernewek, Kernowek | Kernowek | Cornish |

| gwenenen | gwenenen | gwenenenn | gwenen | gwenenen | gwenenen | bee |

| cadar, chayr | chayr, cadar | kador | cader, chair | kador, cador | chair, cadar | chair |

| kēs | cues | keus | keaz | keus | keus | cheese |

| yn-mēs | yn-mēs | yn-mes | a-vêz | yn-mes | in mes | outside |

| codha | codha | koedha | codha | kodha, codha | codha | (to) fall |

| gavar | gavar | gaver | gavar | gaver | gavar | goat |

| chȳ | chȳ | chi | choy, chi, chy | chi, chei | chy | house |

| gwēus | gwēus | gweus | gwelv, gweus | gweus | gweùs | lip |

| aber, ryver | ryver, aber | aber | ryvar | aber | ryver, aber | river mouth |

| nyver | nyver | niver | never | niver | nyver | number |

| peren | peren | perenn | peran | peren | peren | pear |

| scōl | scōl | skol | scoll | skol, scol | scol | school |

| megy | megy | megi | megi | megi, megy | megy | (to) smoke |

| steren | steren | sterenn | steran | steren | steren | star |

| hedhyū | hedhyw | hedhyw | hedhiu | hedhyw | hedhyw | today |

| whybana | whybana | hwibana | wiban, whiban | hwibana, whibana | whybana | (to) whistle |

| whēl | whēl | hwel | whêl 'work' | hwel, whel | whel | quarry |

| lün | luen | leun | lean | leun | leun | full |

| arghans | arhans | arghans | arrans | arhans | arhans | silver |

| arghans, mona | mona, arhans | muna | arghans, mona | arhans, mona | mona | money |

The following table compares Cornish words with their equivalents from its sister Brythonic languages of Welsh and Breton and its cousin languages Irish, Scottish Gaelic and Manx, along with an English gloss.

| Cornish (SWF) | Welsh | Breton | Irish | Scottish Gaelic | Manx | English |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Kernewek, Kernowek | Cernyweg | Kerneveureg | Coirnis | Còrnais | Cornish | Cornish |

| gwenenen | gwenynen | gwenanenn | beach, meach | seillean, beach | shellan | bee |

| kador, cador | cadair | kador | cathaoir | cathair | caair | chair |

| keus | caws | keuz | cáis | càise | caashey | cheese |

| yn-mes | tu fas, tu allan | er-maez | amuigh/amach | a-muigh/a-mach | y-mooie/(y-)magh | outside |

| kodha, codha | codwm | kouezhañ | titim, tuitim | tuiteam | tuittym | (to) fall |

| gaver | gafr | gavr/gaor | gabhar | gobhar/gabhar | goayr | goat |

| chi, chei | tŷ | ti | tigh, teach | taigh | tie | house |

| gweus | gwefus | gweuz | béal 'mouth' | bile | meill | lip |

| aber | aber | aber | inbhear | inbhir | inver | river mouth |

| niver | rhif, nifer | niver | uimhir | àireamh | earroo | number |

| peren | gellygen, peren | perenn | piorra | peur/piar | peear | pear |

| skol, scol | ysgol | skol | scoil | sgoil | scoill | school |

| megi, megy | ysmygu | mogediñ | tabac a chaitheamh | smocainn | smookal | (to) smoke |

| steren | seren | ster(ed)enn | réalt | reult | reealt | star |

| hedhyw | heddiw | hiziv | inniu, inniubh | an-diugh, inniugh | jiu | today |

| hwibana, whibana | chwibanu | c'hwibanat | feadaíl | feadghal | feddanagh | (to) whistle |

| hwel, whel | chwarel | arvez | cairéal | coireall/cuaraidh | quarral | quarry |

| leun | llawn | leun | lán | làn | laan | full |

| arhans | arian | arc'hant | airgead | airgead | argid | silver |

| arhans, mona | arian, pres | moneiz | airgead | airgead | argid | money |

Sample texts

Yma pub den genys frank hag equal yn dynyta hag yn gwyryow. Ymons y enduys gans reson ha keskans hag y tal dhedhans omdhon an eyl orth y gela yn sperys a vredereth.—Article I of the Universal Declaration of Human Rights

Agan Tas ni, eus y’n nev,

bennigys re bo dha hanow.

Re dheffo dha wlaskor,

Dha vodh re bo gwrys y’n nor kepar hag y’n nev.

Ro dhyn ni hedhyw agan bara pub dydh oll,

ha gav dhyn agan kammweyth

kepar dell evyn nyni

dhe’n re na eus ow kammwul er agan pynn ni;

ha na wra agan gorra yn temptashyon,

mes delyrv ni dhiworth drog.

Rag dhiso jy yw an wlaskor,

ha’n galloes ha’n gordhyans,

bys vykken ha bynari.

Yndella re bo!—Pader Agan Arloedh, The Lord's Prayer

Common phrases

The spelling and pronunciation below use the Standard Written Form:

| Cornish | IPA | English |

|---|---|---|

| Myttin da | [ˈmɪttin ˈdaː] | "good morning" |

| Dydh da | [ˈdɪːð ˈdaː] | "good day" |

| Fatla genes? | [ˈfatla ˈɡɛnɛs] | "how are you?" |

| Yn poynt da, meur ras | [ɪn ˈpɔjnt ˈdaː mœːr ˈraːs] | "Well, thank you" |

| Py eur yw? | [ˈpɪː ˈœːr ɪw] | "What time is it?" |

| Ple'ma Rysrudh, mar pleg? | [ˈplɛː maː ˈrɪzryð mar ˈplɛːɡ] | "Where is Redruth please?" |

| Yma Rysrudh ogas dhe Gambron, heb mar! | [ɪˈmaː ˈrɪzryð ˈɔɡas ðɛ ˈɡambrɔn hɛb ˈmaːr] | "Redruth is near Camborne, of course!" |

Culture

The Celtic Congress and Celtic League are groups that advocate cooperation amongst the Celtic Nations in order to protect and promote Celtic languages and cultures, thus working in the interests of the Cornish language.

There have been many films, some televised, made entirely, or significantly, in the language. Many businesses use Cornish names. The overnight medical service in Cornwall is now called Kernow Urgent Care.

Cultural events

Cornwall has many cultural events associated with the language, including the international Celtic film festival, hosted in St Ives in 1997, with the programme in Cornish, English and French. The Old Cornwall Society has promoted the use of the language for many years at annual events and meetings. Two examples of ceremonies that are performed in both the English and Cornish languages are Crying The Neck[54] and the annual mid-summer bonfires.[55]

Study and teaching

Cornish is taught in some schools; it was previously taught at degree level in the University of Wales, though the only existing courses in the language at University level are as part of a course in Cornish Studies at the University of Exeter, or as part of the distance-learning Welsh degree from the University of Wales, Lampeter. In March 2008, Benjamin Bruch started teaching the language as part of the Celtic Studies curriculum at the University of Vienna, Austria.

Cornwall's first Cornish language creche was established in 2010 at Cornwall College, Camborne. The nursery teaches children aged between two and five years alongside their parents, to ensure the language is also spoken in the home.[13]

Government recognition

The Cornish language has been recognised as a minority language by the UK government under the European Charter for Regional or Minority Languages. This follows years of pressure by interest groups such as Mebyon Kernow and Kesva an Taves Kernewek.

Books in Cornish

A first complete edition of the New Testament in Cornish, Nicholas Williams' translation of the Testament Noweth agan Arluth ha Savyour Jesu Cryst, was published at Easter 2002 by Spyrys a Gernow (ISBN 0-9535975-4-7); it uses Unified Cornish Revised orthography. The translation was made from the Greek text, and incorporated John Tregear's existing translations with slight revisions.

In August 2004, Kesva an Taves Kernewek published another Cornish translation of the New Testament (ISBN 1-902917-33-2), translated by six Bards of Gorseth Kernow under the leadership of Keith Syed; it uses Kernewek Kemmyn orthography. It was launched in a ceremony in Truro Cathedral attended by the Archbishop of Canterbury.

A few small publishers produce books in Cornish which are stocked in some local bookshops.

Musical works

English composer Peter Warlock, an enthusiast of the Celtic languages, wrote a Christmas carol in Cornish (setting words by Henry Jenner). Cornish musician Jory Bennett (born Redruth, 1963) has composed "Six Songs of Cornwall" for bass and piano, a Cornish song-cycle, settings of Cornish language poems by Nicholas Williams /trans. E. G. Retallack Hooper (f.p. Keele University, 7 May 1986). The Cornish electronic musician Richard D James has often used Cornish names for track titles, most notably on his DrukQs album. Gwenno Saunders is a multilingual Welsh-born musician and a Cornish speaker.

See also

- Cornish literature

- List of Celtic language media

- Languages in the United Kingdom

- List of topics related to Cornwall

- Language revival

- The Cornish Language Council (Cussel an Tavas Kernuak)

- European Charter for Regional or Minority Languages

- Irish language revival

References

- ↑ 1.0 1.1 "'South West:TeachingEnglish:British Council:BBC". BBC/British Council website (BBC). 2010. http://www.teachingenglish.org.uk/uk-languages/south-west. Retrieved 2010-02-09.

- ↑ http://www.cornish-language.org/english/faq.asp

- ↑ 3.0 3.1 Rebuilding the Celtic languages By Diarmuid O'Néill (Page 222)

- ↑ 4.0 4.1 Diarmuid O'Neill. Rebuilding the Celtic Languages: Reversing Language Shift in the Celtic Countries. Y Lolfa. p. 240. ISBN 0862437237. http://books.google.co.uk/books?id=6PFckH-GBKAC&pg=PA212&dq=%22Predennek%22&ei=wUZ6SfW0EJX8ygS3kO2oBg#PPA240,M1.

- ↑ Cornish Language Partnership: Music

- ↑ Cornish Language Partnership: Film clips

- ↑ Ethnologue - Cornish

- ↑ This is the Westcountry - Cornish language - is it dead?

- ↑ BBC News - Cornish gains official recognition

- ↑ BBC News - Breakthrough for Cornish language

- ↑ Have a good dy: Cornish language is taught in nursery - Times Online, 15 Jan 2010

- ↑ Diarmuid O'Neill. Rebuilding the Celtic Languages: Reversing Language Shift in the Celtic Countries. Y Lolfa. p. 242. ISBN 0862437237. http://books.google.co.uk/books?id=6PFckH-GBKAC&pg=PA212&dq=%22Predennek%22&ei=wUZ6SfW0EJX8ygS3kO2oBg#PPA240,M1.

- ↑ 13.0 13.1 "'WalesOnline - News - Wales News - First Cornish-speaking creche is inspired by". WalesOnline website (Welsh Media Ltd). 2010-01-16. http://www.walesonline.co.uk/news/wales-news/2010/01/16/first-cornish-speaking-creche-is-inspired-by-example-set-inwales-91466-25612689/. Retrieved 2010-01-18.

- ↑ http://www.gosw.gov.uk/497666/docs/254795/mode_of_use.doc

- ↑ UNESCO Atlas of World Languages' decision to brand Cornish as "extinct"

- ↑ UNESCO Atlas of World Languages' reconsideration of status of Cornish language

- ↑ BBC News - June 2005 - Cash boost for Cornish language

- ↑ Suppression of Cornish identity and language

- ↑ Jackson, Kenneth (1953). Language and History in Early Britain. Edinburgh: Edinburgh University Press.

- ↑ 20.0 20.1 Payton, Philip Cornwall. Fowey: Alexander Associates (1996).

- ↑ Cornwall Council timeline 927-936

- ↑ Estimate by Ken George

- ↑ Oxford scholars detect earliest record of Cornish

- ↑ Sims-Williams, P., 'A New Brittonic Gloss on Boethius: ud rocashaas', Cambrian Medieval Celtic Studies 50 (Winter 2005), 77-86.

- ↑ Jenner, Henry (1904) A Handbook of the Cornish Language chiefly in its latest stages with some account of its history and literature. London: David Nutt

- ↑ Richard Carew's Survey of Cornwall, 1602

- ↑ SW7112 : St Wynwallow's Church, Landewednack, at geograph.org.uk

- ↑ Googlebooks Survey of Cornwall By Richard Carew (page 152)

- ↑ Ellis, P. B. (1974) The Cornish Language. London: Routledge; p. 80

- ↑ Peter Berresford Ellis, The Cornish language and its literature, pp. 115-116 online

- ↑ Berresford Ellis, op. cit., p. 125 online

- ↑ John Bannister, Cornish Place Names (1871)

- ↑ Lach-Szyrma, W. S. (1875) "The Numerals in Old Cornish". In: Academy, London, 20 Mar 1875 (quoted in Ellis, P. B. (1974) The Cornish Language, p. 127)

- ↑ The Cornish Language and Its Literature: a History, by Peter Berresford Ellis

- ↑ Independent Study on Cornish Language

- ↑ Graves, Eugene van T. (ed.) (1964) The Old Cornish Vocabulary. Ann Arbor, Mich: Univ. M/films

- ↑ Discovering local history By David Iredale, John Barrett (page 44)

- ↑ Ellis, P. B. (1974); pp. 82-94

- ↑ Lhuyd, Edward (1707) Archæologia Britannica: giving some account additional to what has been hitherto publish'd, of the languages, histories and customs of the original inhabitants of Great Britain, from collections and observations in travels through Wales, Cornwal, Bas-Bretagne, Ireland, and Scotland; Vol. I. Glossography. Oxford: printed at the Theater for the author, and sold by Mr. Bateman, London

- ↑ Ellis, P. B. (1974); pp. 100-08

- ↑ Lhuyd, Edward (1702) [Elegy on the death of King William III, in Cornish verse] in: Pietas Universitatis Oxoniensis in obitum augustissimi Regis Gulielmi III; et gratulatio in exoptatissimam serenissimae Annæ Reginæ inaugurationem. Oxonii: e Theatro Sheldoniano

- ↑ Jago, Fred W. P. (1882) The Ancient Language and the Dialect of Cornwall. New York: AMS Press, 1983, (originally published 1882, Netherton and Worth, Truro), pp. 4 ff.

- ↑ 43.0 43.1 43.2 http://www.cornishlanguage.co.uk/history.htm

- ↑ Kernowek official website

- ↑ "This is Cornwall" website

- ↑ 46.0 46.1 Kernowek Standard website

- ↑ Kernowek Dasunys website

- ↑ Breakthrough for Cornish language BBC News, 19 May 2008

- ↑ An Outline of the Standard Written Form of Cornish Maga Kernow

- ↑ BBC News 19 May 2008 - Breakthrough for Cornish language

- ↑ BBC News 19 May 2008 - Standard Cornish spelling agreed

- ↑ Cornish Language Partnership - Standard Written Form Ratified

- ↑ Cornish Language Partnership - Outline of SWF (pdf)

- ↑ Crying the Neck in Cornwall

- ↑ Redruth Old Cornwall Society

Bibliography

- F. W. P. Jago, A Cornish Dictionary (1887)

- Ellis, Peter B. (1974) The Cornish Language and its Literature. ix, 230 p. London: Routledge & Kegan Paul

- Ellis, Peter B. (1971) The Story of the Cornish Language. 32 p. Truro: Tor Mark Press

- Jackson, Kenneth (1953) Language and History in Early Britain: a chronological survey of the Brittonic languages, first to twelfth century a.D. Edinburgh: U. P. 2nd ed. Dublin : Four Courts Press, 1994 has a new introduction by William Gillies

- Sandercock, Graham (1996) A Very Brief History of the Cornish Language. Hayle: Kesva an Tavas Kernewek ISBN 0907064612

- Weatherhill, Craig (1995) Cornish Place Names & Language. Wilmslow: Sigma Press (reissued in 1998, 2000 ISBN 1-85058-462-1; second revised edition 2007 ISBN 978-1-85058-837-5)

External links

- A Handbook of the Cornish Language, by Henry Jenner A Project Gutenberg eBook

- Cornish Language Partnership website

- A Cornish Internet radio station in nascent state featuring weekly podcasts in Cornish

- Spellyans - Standard Written Form Cornish discussion list

- UdnFormScrefys' site for the proposed compromise orthography, Kernowek Standard

- List of localized software in Cornish

- Blas Kernewek - A Taste of Cornish - basic Cornish lessons hosted by BBC Cornwall

- Cornish Language Fellowship

- Cornish today by Kenneth MacKinnon - from the BBC

- Bibel Kernewek Cornish Bible Translation Project

- Cowethas Peran Sans Cornish Christian fellowship promoting use of Cornish in prayer and worship

Dictionaries

- Cornish-English Dictionary: from Webster's Online Dictionary - The Rosetta Edition.

- Lexicon Cornu-Britannicum: a Dictionary of the Ancient Celtic Language of Cornwall by Robert Williams, Llandovery, 1865.

- Cornish-English Dictionary

|

||||||||||||||||||||

|

|||||||||||||||||

|

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||